In today’s push toward digital technology in education, we often ask: How can technology support—not replace—student engagement, dialogue and creativity? My colleague Lene Illum and I are asking ourselves how to design for students voices and dialogue in writing practices in school. As part of our research we believe that meaningful answers lie in the intersection of the tangible and the digital. We have developed SkriveXpeditionen (The WritingXpedition) that draws on both these aspects.

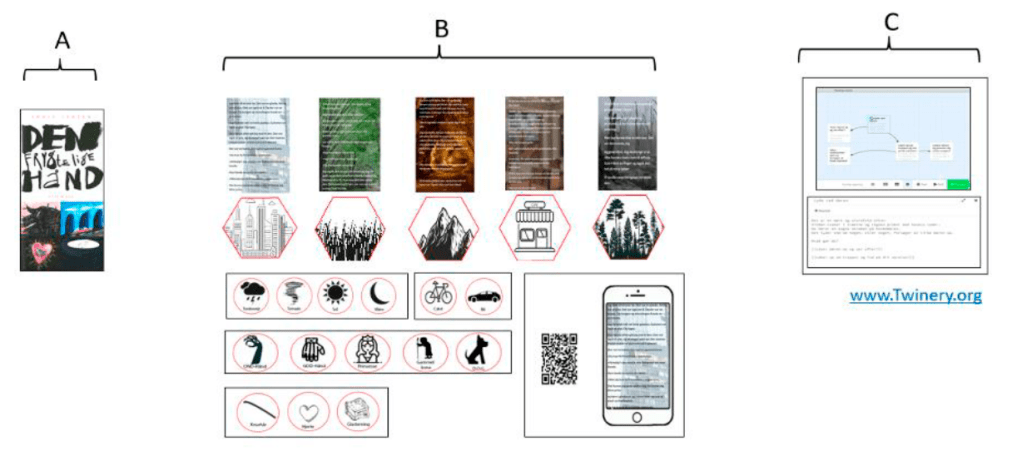

SkriveXpeditionen is a didactic design developed to support creative and dialogic writing processes in Danish L1 classrooms at the intermediate level (typically grade 5) with an age group of 11-12 years. The design combines physical and digital tools to scaffold students’ narrative thinking, collaborative dialogue, and creative expression.

Skrive consists of two main elements.

First, a set of physical wooden tiles. These tiles are engraved with various narrative motifs and symbolic images. Some tiles include QR codes that link to excerpts from a shared literary starting text. The tiles function as tactile prompts that help students:

- Generate and structure ideas

- Decompose narrative elements

- Visualise connections and develop plot structures

Secondly, the open-source interactive writing tool Twine. Twine enables students to create non-linear, interactive stories, where readers make choices that affect the outcome. The platform invites computational thinking through sequencing, logic, and hypertext structure, while simultaneously encouraging literary creativity.

In the image, the pedagogical design is displayed. A is the starting point where students get a short read-out-loud from the beginning of a novel. In this case, it is “The Horrible Hand”, a fantasy novel. B represents the wooden pieces and the phase where students engage and collaborate on their stories. Finally C represents the process of creating their stories in Twine.

The Pedagogical Rationale

SkriveXpeditionen is designed to cultivate what Neil Mercer calls exploratory talk: a form of dialogue where students collectively explore, justify, and refine ideas. The material artefacts serve as mediators that bring students’ ideas into a shared dialogic space. The goal is not only to support writing outcomes but to:

- Enhance oral language development

- Foster embodied and multimodal communication

- Promote partner-awareness and collaborative meaning-making

Learning Outcomes and Observations

Preliminary findings from classroom interventions show that SkriveXpeditionen:

- Strengthens students’ engagement in the writing process

- Encourages playful experimentation and co-creation

- Supports students in structuring stories and making narrative decisions

- Increases participation opportunities, especially for students who might struggle with traditional writing tasks

The design also reveals how materiality—in the form of physical tiles—can play a central role in shaping dialogic learning environments and computational literacy practices.

SkriveXpeditionen is more than a writing tool. It is a hybrid learning design that brings together literature, technology, and embodied dialogue to support student creativity and collaboration. By combining material and digital media, it opens new pedagogical pathways for teaching writing in ways that are meaningful, imaginative, and deeply social.

Enhancing Computational Literacy through objects to think with.

SkriveXpeditionen is a teaching design that invites students into a creative and exploratory learning space, where storytelling and technology are tightly interwoven. Drawing on Andrea diSessa’s concept of computational literacy, learning is understood here as a materially-supported deployment of skills and dispositions toward meaningful intellectual goals.

Unlike the narrower notion of computational thinking, often framed as a general set of problem-solving skills, computational literacy expands the view by emphasising three interrelated dimensions: the cognitive, the social, and the material. These dimensions are not separate layers but intertwined aspects of how learners engage with the world.

SkriveXpeditionen brings all three dimensions into play. The physical wooden tiles serve as cognitive scaffolds, allowing students to break down and recompose narrative ideas. Group work and conversation create a shared space where meaning is socially negotiated. At the same time, both the tiles and the Twine platform act as material mediators, giving shape to students’ abstract thinking and enabling new forms of interaction and expression.

In this interplay, students do not merely write stories—they engage in thinking through materials. They work with narrative elements, symbols, and code to construct meaning within a shared ecology of learning. It is precisely within this process that what Seymour Papert called powerful ideas begin to emerge.

Students learn how ideas evolve in collaboration and dialogue, as they articulate and refine their thinking through shared language, gesture, and embodied interaction. They work with narrative systems, grappling with cause-effect relationships, branching logic, and interactive structures—not as abstract concepts, but through concrete storytelling practices. They also explore how representational elements can be rearranged and transformed, discovering that story components are not fixed but fluid and malleable.

SkriveXpeditionen is not about teaching programming per se. Instead, it aligns with Papert’s deeper pedagogical vision of using technology as a medium for expression, a tool for exploration, and a mirror for thinking.

We will continue our research and development

Lene and I will continue our endeavour into SkriveXpeditionen and how to enhance and develop the design. Next steps for us is to focus on a more generic concept that can be applied to a vararity of texts in L1.

Stay tuned!