Computational thinking (CT) has become a buzzword in educational policy and curriculum reform. Promoted as a fundamental 21st-century skill, it is often described as a universal way of thinking—akin to literacy and numeracy. But beneath this seemingly neutral framing lies a deeper question: What kind of thinking do we want students to engage in, and what role should schools play in nurturing it?

The current dominant view of CT, popularised by Jeannette Wing, sees it as a set of abstract, transferable skills drawn from computer science—algorithmic thinking, abstraction, problem decomposition. This approach fits neatly into existing curricular structures and assessment regimes, but it risks sidelining the messier, more situated, and culturally embedded dimensions of learning with and through computers.

An alternative perspective comes from Seymour Papert, whose work in the 1970s and 80s laid the groundwork for what we now call CT. Papert didn’t frame CT as a fixed set of skills. Instead, he was concerned with thinking deeply about thinking itself—learning through making, experimenting, and expressing ideas in computational media. His approach, known as constructionism, was grounded in the idea that children learn best when they are actively engaged in building things that are meaningful to them.

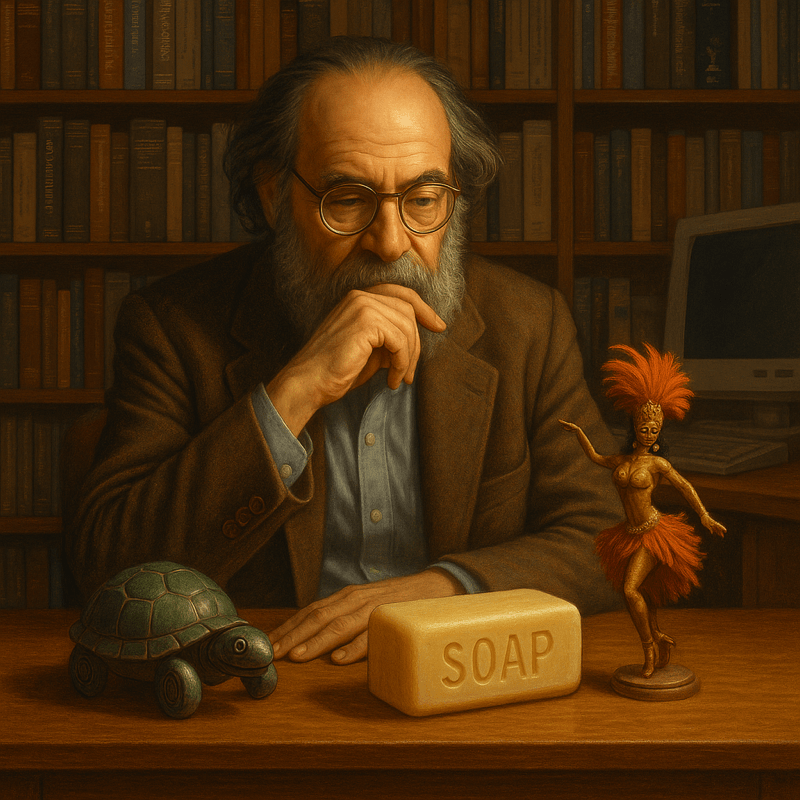

Ai generated image in ChatGPT displaying three themes Papert’s development of constructionism. The Tutle Program, Soap Sculptures and Samba Schools.

Our educational system rejects the “false theories” of children, thereby rejecting the way children really learn. (Papert, Mindstorms 1980)

Central to Papert’s vision were what he called “objects-to-think-with”—tangible or digital artefacts that serve as tools for thought. These could be programmable turtles on the screen, floor robots, or soap sculptures. The key is that learners engage with these objects not through instruction, but through exploration and iteration. The act of programming becomes a medium for expressing ideas, testing hypotheses, and developing personal and shared understandings.

Papert’s notion of epistemological pluralism is equally crucial. He recognised that learners approach problems in different ways—some prefer planning and abstraction, others tinker and iterate. Both styles are valid, and a healthy learning environment supports this diversity. In contrast, much of today’s CT implementation privileges the abstract, logical, and formal, often marginalising intuitive, creative, or sensory approaches to computational problem-solving.

Another critical insight from Papert is his view of schools as cultural institutions with deeply ingrained norms. He was sceptical of how technologies—computers included—tend to be absorbed into existing school structures rather than transforming them. He warned against what he called technocentrism—the belief that technological tools alone can drive educational change. For Papert, the real power of the computer lay not in the machine itself, but in its potential to disrupt traditional pedagogies and empower learners.

Little by little the subversive features of the computer were eroded away: Instead of cutting across and so challenging the very idea of subject boundaries, the computer now defined a new subject; instead of changing the emphasis from impersonal curriculum to excited live exploration by students, the computer was now used to reinforce School’s ways. What had started as a subversive instrument of change was neutralized by the system and converted into an instrument of consolidation (Papert, The Children’s Machine, 1993)

Papert’s vision of a “Samba School for Computing” offers a compelling metaphor. Inspired by the inclusive, community-based learning culture of Brazilian samba schools, he imagined computational learning as a pluralistic, joyful, and participatory activity. Instead of rigid curricula and standardised assessment, imagine spaces where children and adults collaboratively explore, build, play, and perform with computational media—learning not just to code, but to express, critique, and co-create.

This vision remains deeply relevant today. While CT is often justified by its economic utility—preparing students for future jobs—Papert reminds us that schools should not merely serve existing societal needs. They should be spaces for reimagining society itself. Rather than training students to think like computer scientists, we might ask how computation can support them in thinking like designers, storytellers, activists, or citizens.

Moreover, Papert’s critique of the school’s “immune system”—its tendency to neutralise radical ideas—is as pertinent as ever. Today’s digital tools are often used to reinforce traditional instruction rather than to reimagine it. Many implementations of CT end up focusing on tool mastery rather than tool invention, reinforcing rather than disrupting existing power structures in education.

A genuinely transformative approach to CT would begin not with abstract definitions but with concrete engagements: what are learners passionate about? What problems do they want to solve? What stories do they want to tell? From there, educators can scaffold experiences that build computational fluency in ways that are meaningful and contextually grounded.

Key Takeaways for Schools Today:

- Reframe CT as situated practice Rather than treating computational thinking as a decontextualised skill set, we should design learning environments that situate CT in meaningful, hands-on, and culturally relevant practices.

- Value epistemological diversity Support different ways of knowing and thinking. Not all students thrive through abstraction—some learn best through tinkering, storytelling, or physical interaction with materials. All of these are valid pathways into computational understanding.

- Challenge the school’s “immune system” Schools must remain open to educational models that challenge the status quo. CT has the potential to democratise and humanise learning—if we resist the urge to reduce it to testable outcomes and instead embrace it as a medium for expression, reflection, and cultural participation.